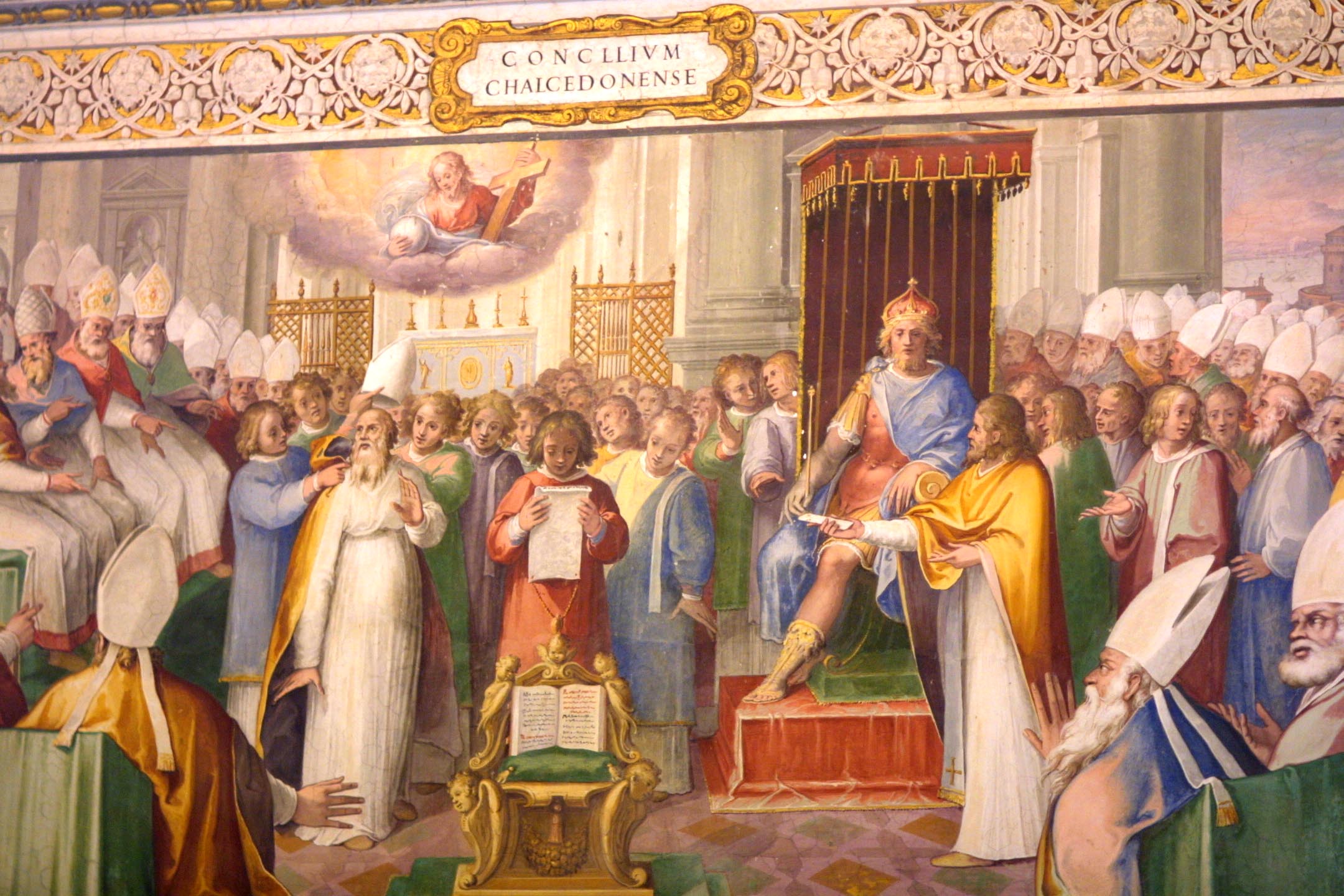

I am in the midst of a series of articles on the seven ecumenical councils of the early church. These councils commenced with the First Council of Nicaea in 325 and concluded with the Second Council of Nicaea in 787. Between these two events were five more, each of which attempted to understand and establish a unified Christian theology.

In this series we are taking a brief look at each of the seven councils. For each one we are considering the setting and purpose, the major characters, the nature of the conflict, and then the results and lasting significance. We continue today with the the fourth council, the Council of Chalcedon.

SETTING & PURPOSE

In 449, a Second Council of Ephesus was convened because of the excommunication of a monk named Eutyches, who taught that Christ, after his incarnation, had only one nature. The council itself devolved into drama when those who supported Eutychus, led by Dioscorus and supported by the Roman Emperor Theodosius II, unilaterally and forcefully asserted their doctrine over against those who held the orthodox view that Christ has two natures—one fully human and one fully divine—which exist in hypostasis in one person. When news of the council reached Rome, Pope Leo immediately termed it Latrocinium (a “robber council”).

When Marcian, an orthodox Christian, became emperor, he wished to convene another council in order to resolve the turmoil that the Second Council of Ephesus had stirred up. That council met from October 8 to November 1, 451, in Chalcedon, now a district of modern-day Istanbul. It was held here rather than in Italy because of the pressing threat to the Roman Empire from Attila and his Huns.

by

by